WebAuthn Attestation and Authenticator Metadata

What is attestation?

Colloquially speaking, “attestation” is a term used to convey proof or evidence of something. Within the context of WebAuthn, it refers to the ability of a security device to prove its own identity and for a Relying Party (RP) to attain evidence regarding the provenance of a credential set, namely details about the security device it was created on, and furthermore, which manufacturer actually created said device. Attestation only takes place when a new security device is first nominated as an authenticator, typically during an account registration ceremony.

The attestation of a security device is facilitated by its digital attestation certificate, which exposes details such as its make and model but more importantly the public key component of a key pair imported by the manufacturer during production. An attestation certificate is always specific to a company or model, for example, all YubiKey 5 series devices created within the same production batch possess the same attestation certificate, and similarly, an attestation certificate is shared amongst all iPhone 12 Pro devices produced in a batch. Ultimately, an attestation can always be used to cryptographically assert that a specific security device is being used when it is registered.

It is important to note that WebAuthn strives for an equal balance of security and privacy, and disincentivizes any mechanism that makes security keys uniquely identifiable. As such, in order to preserve user privacy and limit the ability of an RP to identify a user based solely on the attestation certificate presented during registration, FIDO guidance recommends to all manufacturers that each attestation certificate span at least 100,000 distributed devices within any given batch.

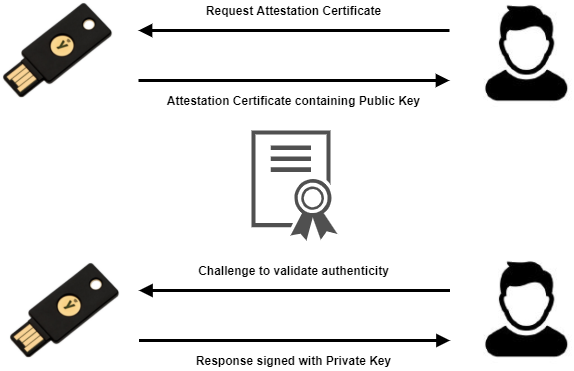

Figure 1 - The Attestation Certificate request and the subsequent validation processes during a typical WebAuthn registration ceremony

Without delving too far into the technical details, the response message supplied by a WebAuthn authenticator at the conclusion of a registration ceremony, will always include a signature based on the attestation private key from the device itself, in addition to the aforementioned digital attestation certificate. The purpose of the signature is to prevent an attacker (or other third party) from simply exporting the attestation certificate of a known or trusted authenticator and passing it off as the attestation certificate of another device.

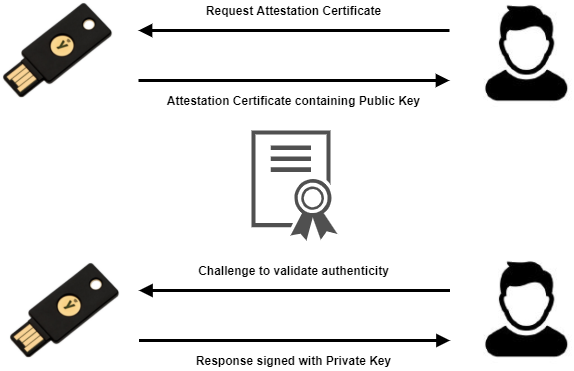

Figure 2 - The structure of a registration response message

As depicted in Figure 2, the response message is composed of several blocks - the attestation certificate as a standard X.509 encoded certificate and the accompanying signature created with the attestation private key, comprise the back half. In order to validate the attestation offered by a security device, the public key is extracted from within the attestation certificate and then used to verify the signature of the response.

If the response signature can be successfully verified, the attestation certificate itself should then be verified for legitimacy. In similar fashion to the registration response message signature validation, the idea is to identify and extract the issuer responsible for creating the certificate as specified within the attestation certificate, matching it against the issuer’s known public key, and finally, using it to verify the signature on the attestation certificate itself. Note that the process may need to be repeated until a clear chain of trust is mapped out from the issuer to a trusted root CA.

If all these verifications are successful, the newly created registration keypair can be cryptographically tied to the attestation certificate, and the attestation certificate in turn, may be cryptographically tied to a trusted root CA. Assuming a level of assurance that a particular vendor has properly manufactured their authenticators so that the attestation private key has not been compromised, an RP should have a high degree of confidence that an authenticator is in fact, authentic.

As a final note, the WebAuthn verification component within most RP implementations support attestation directly, requiring only the attestation object and associated metadata to complete the entire verification against a known vendor. The method for doing so will like vary between deployments however, so it is recommended to always refer to the specific documentation applicable to the underlying RP itself.

Why is attestation important?

From the perspective of an RP or a security administrator, attestation provides the ability to understand how much trust to put in a particular set of credentials (security device) and subsequently, make informed decisions based on the collective profile of attestation certificates being used. Attestation may also be critical to both users and organizations when nominating or purchasing a security device, if best in class security and reputation is top of mind.

To help illustrate, if an exploit or vulnerability is found in relation to a series of devices or perhaps one affecting an entire manufacturer, an RP has the ability to easily identify any affected accounts and enact a mitigation policy accordingly, assuming attestation information is collected and stored during registration. If the problem is eventually addressed or resolved, the RP can then easily reverse course or even implement an entirely new policy without much disruption to non-affected accounts.

In some instances, if an attestation certificate is self-signed, then there may be a generally diminished level of assurance than would be the case with a certificate signed by a trusted manufacturer such as Yubico or a known root CA. As a result, an RP may choose to pre-configure a warning to users during registration that a nominated device is not trusted according to its sources.

Furthermore, for some heavily regulated services such as those in the financial industry or the public sector, an RP could be required to know more about the devices that are accessing it so that it may enforce stricter policies. Due to the extremely sensitive nature of the underlying data, these services must guarantee that cryptographic keys are secure, that biometrics are of a certain level of accuracy or that devices have been adequately certified, which can only be achieved if the registration request is coming from a known and trusted model of FIDO authenticator.

What are the use cases for attestation?

During a WebAuthn account registration ceremony, the unique model number of a nominated security device is sent to the RP alongside the newly created public key used to access that specific service (not to be mistaken for the attestation key). The unique model number is also known as the “Authenticator Attestation Globally Unique ID” (AAGUID), and upon receiving this unique identifier, the RP is able to look up a metadata statement from a service such as the FIDO Metadata Service (MDS) or potentially a JSON configuration file to complete the discovery of the nominated security device. Every record within these services will have an AAGUID that corresponds to a known device.

Assuming that the signature associated with the attestation certificate containing the public key is correct and that the certificate chain is validated to a trusted CA, a service can then use the collected metadata about the device for one of several use cases.

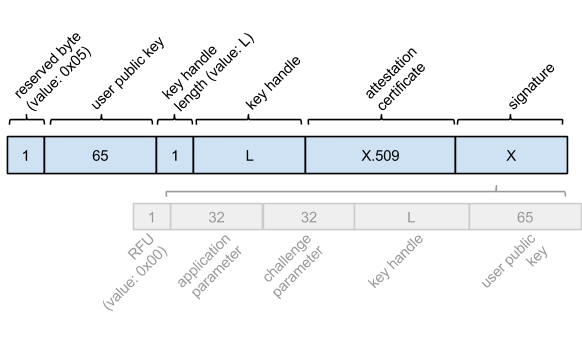

Figure 3 - Attestation provides the option to allow or deny any security devices based on the AAGUID or Attestation Certificate

The first of which is an "allow list", whereby only a limited and pre-defined subset of all security devices may be registered and used as an authenticator in conjunction with a particular service. Depending on policies and how broad the array of security devices is amongst the userbase, this may be the most secure option to weed out potential issues created by untrusted security devices. One such example might be a strict requirement for a U.S. Federal agency mandated by Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS) in order to protect sensitive or valuable data. Furthermore, allowed FIDO authenticators are usually those that have been tested internally or during development and have been vetted as a secure and compatible option.

The second use case, which is similar to the first, is a "deny list", which preemptively blocks a subset of all security devices instead. The benefit or advantage of this approach compared to the first is its more inclusive stance to security devices across the userbase but conversely, the major disadvantage is that it allows untrusted devices to be registered as well. Proponents of this approach aim to avoid alienating or preventing users from registering for the service and intend to only explicitly deny devices that have been flagged or outed as insecure alternatives.

The third and final use case discussed here is what can be generally referred to as "security advisory". The intention is that neither an allow or deny list is implemented but information is merely gathered and stored for the purposes of analyzing the data. The information may, of course, still be used at a later time to either allow or deny specific security devices, but the primary goal is to collate data, suggest to users if there are any potential issues with their registered devices and have a mechanism in place that may lead to prudent action when required.

Attestation guidance and suggestions

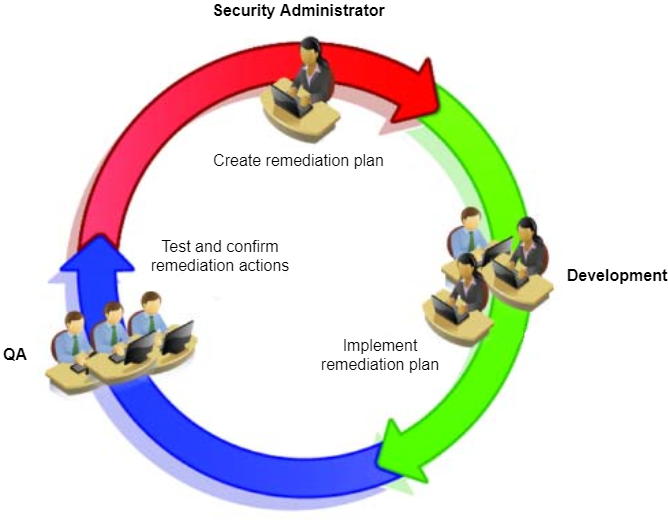

The first and foremost recommendation is to always implement a security advisory stance with regards to attestation at a bare minimum. A large percentage of currently implemented WebAuthn services do not even collect AAGUID during the registration ceremony, which presents itself as a missed opportunity as there is very little down side to simply discovering more information about the security devices being presented. As part of the job description, security administrators should be able to identify and report which FIDO authenticator models are in use and create a remediation plan if issues are discovered which affect particular makes and models. Ostensibly, this can only come to pass if attestation and AAGUID information is collected and stored.

Additionally, one of the many possible attributes available from the MDS and JSON files is the “Attachment” or “Transport” Hint, which indicates all of the communication modes supported by a specific security device, such as NFC, Bluetooth or USB. This information can be used to tailor or customize process flow during either the registration or authentication processes, leading to an improved overall User Experience (UX). As an example, automated suggestions can be sent to users indicating that plugging a device into an available USB port is an option if NFC issues are encountered.

Last but not least, security administrators should periodically check if any of the authenticator models in use have reported issues that may require action. Depending on the implementation, this may mean revoking devices from the allow list, adding devices to the deny list or simply engaging and notifying the relevant resources that remediation is required to prevent potential security issues.

Remediation plan in the event of an authenticator issue Transparency is likely the most important aspect of remediation, and includes notifying or warning users that an issue has been discovered which may lead to weaknesses with regards to their account security. From there, it is not clear what the best approach may be, as it largely depends on RP specific policies and the overall scope of the issue.

One potential outcome however, may be to block all future registrations if users attempt to use an affected authenticator, meanwhile assisting existing users to revoke said devices and even guide them to a new registration using an unaffected security device. Generally, it may be even helpful to suggest that users should associate multiple methods of authentication from the very beginning, so that revoking one method will be less disruptive, as users will already have an alternate path to authentication.

It is critical to recognize that an issue with one particular security device make and/or model is not indicative or inclusive of all devices, and that attestation and remediation are only two key components in running a well oiled and secure authentication machine.

Figure 4 - A typical remediation cycle once a potential issue or problem has been identified

All of the information discussed to this point is only intended as cursory or introductory, but fortunately many other sites and publications out there discuss WebAuthn attestation in greater detail. Below is a list of recommended readings for any developers looking for additional resources, but is by no means exhaustive!

-

As mentioned, all reputable FIDO security device manufacturers carry their own version, but as an example, the Yubico FIDO attestation certificate (which has been signed by Yubico’s root CA) can be found here and may be a great starting point

-

AAGUID information is freely available from The FIDO Alliance Metadata Service

-

The official W3C WebAuthn Specification and API is a great resource for developers looking to scope the entire breadth of the protocol

-

Ackermann Yuriy, a leading figure in FIDO research and standards, has a dedicated site detailing many of the intricacies with regards to attestation that can be found here. It would be beneficial to even experienced WebAuthn developers to spend some time to read his publications