Platform and Roaming Authenticators

A variety of form factors

Modern authenticators arrive in many shapes and sizes, which comes as no real surprise as two of the predominant underlying protocols - FIDO U2F and FIDO2 - are open authentication standards that do not contain any rigid specifications with regards to form factor. The increasing momentum towards these strong authentication approaches and the need to convey compliance of the standards, prompted the creation of the FIDO Alliance Certification, but even that merely helps to serve as an indicator of quality rather than a prescription of construction.

Figure 1 - Authenticators are awarded a FIDO Alliance Certification when all of the security criteria is satisfied

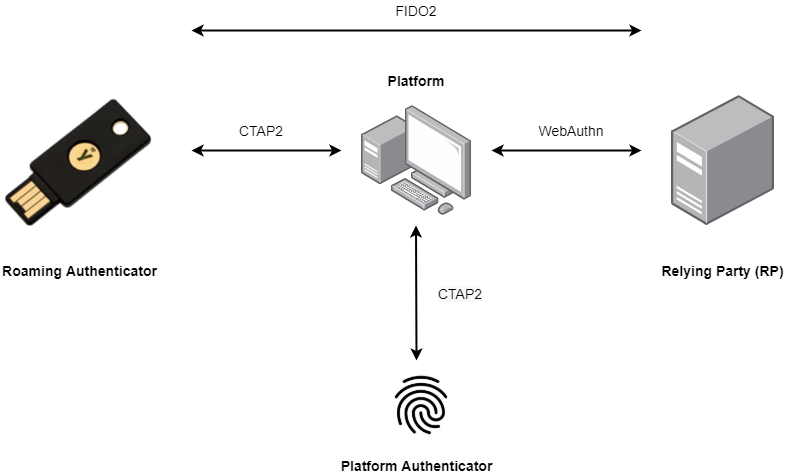

Although FIDO U2F is still widely used to facilitate robust Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA), the newer FIDO2 standard builds upon it by adding passwordless capabilities. But taking a step back, FIDO2 is in fact the umbrella term used to describe an amalgamation of two individual sets of specifications, namely WebAuthn and the Client-to-Authenticator Protocol (currently version 2 - denoted as simply CTAP2 - and iterates on CTAP1 from FIDO U2F). While the WebAuthn component provides a narrow scope of flexibility for developers on the service layer and encompasses the logical interactions across a network, CTAP2 has a much more broad set of standards between a security device and the user, thus giving manufacturers much more agency to interpret the physical designs leading to a greater number of representations. Overall however, the FIDO2 landscape can be categorized into two base types of authenticator.

Figure 2 - FIDO2 is comprised of CTAP2 and WebAuthn

Platform authenticators, also known as internal authenticators, are those embedded into other devices and cannot be decoupled without deconstructing or destroying the hardware. Examples of this class of authenticator include Apple’s Touch ID and Face ID, Windows Hello and even the common fingerprint scanner found on many laptops. Platform authenticators have a built-in Trusted Platform Module (TPM) used to secure any generated private keys and are often biometric in nature, although this is certainly not a requirement. When present however, the biometric element provides a mechanism for the platform to match against the device’s identity profile of a user, and in turn, use the stored cryptographic credentials to authenticate against a Relying Party (RP). When it is not present, the same outcome can be achieved with other techniques such as the traditional Personal Identification Number (PIN) for instance, although potentially, may be less secure since they are vulnerable to shoulder surfing.

Figure 3 - Face ID was first introduced by Apple for the iPhone X but remains a crucial security element even in the later models

Roaming authenticators, sometimes referred to as cross-platform or external authenticators, refer to those that are not tied to any one particular platform but can be used to authenticate across multiple devices. The quintessential example is a hardware security key, such as the YubiKey. These too possess an integrated secure crypto-processor, similar to the TPM used in a platform authenticator, but one that is specifically designed to be mobile (i.e. smaller in size) and accommodate authentication without a fixed anchor point.

The idea of this category of authenticator is to enable users to create a pathway to the root of trust, but immediately delegate some of that trust to an associated device or platform during registration, as roaming authenticator themselves are unable to complete the entire end-to-end authentication process. As such, the user can often authenticate themselves by simply presenting the security device, and then authorizing other devices to complete the process on its behalf in subsequent sessions (referred to as "bootstrapping"). In the event a roaming authenticator is lost or destroyed (assuming of course, the user has recourse to an alternate or secondary means to authenticate to their account), the device itself can be logically revoked, in addition to any bootstrapped devices.

Figure 4 - A keychain with a standard set of keys in addition to a YubiKey 5 NFC

There is no blanket response or default answer to which type of authenticator is most suitable for a particular user or even group, as it largely depends on the available resources, the relevant policies and the features considered to be most important. Instead, the best way to illustrate or determine the answer inevitably comes down to the use cases and intended applications.

Platform authenticators generally apply to situations where only one specific device is to be designated as trusted against an RP, and will often be a user’s laptop or mobile phone for instance. Once the initial registration ceremony has been completed, the device itself becomes an integral component when authenticating to any future sessions, and will be able to represent the user implicitly as the second factor within the authentication process. The complete integration of the platform authenticator’s physical form and functionality into the physical device itself, serves only to increase the ease of use and potentially removes the barriers to entry for any RP deploying an authentication scheme with high marks in the User Experience (UX) category.

The use cases for roaming authenticators are numerous, including authentication on seldom used devices that a user may not necessarily want to be retained as trusted in case it may become compromised in the future, a public device that is shared amongst multiple users (for example, a terminal in a public library), temporarily use kiosks (such as a cashier’s counter at a large retail store) or devices that do not themselves include a platform authenticator (i.e. most older devices are without facial or fingerprint scanning technology). In some policy mandated situations, it could even be the case that authenticators are strictly required to be kept separate from network connected devices as a means to further insulate a user or enterprise from potential remote attacks or breaches. A roaming authenticator is also an ideal candidate to store backup credentials in case a primary (platform) authenticator is stolen or lost, which can happen somewhat frequently with laptops and mobile phones.

Implementation guidance

As more and more authenticators flood the market, it may seem daunting to navigate the myriad of obstacles scattered along the way to a fully functional authentication flow which caters to both platform and roaming authenticator types. To alleviate some of the anxiety, below are some general points to guide and assist developers and security administrators alike.

Authenticator Attestation

Attestation provides means for an RP to verify and validate that a set of credentials was created on a device manufactured by a trusted party. Furthermore, it also allows a way to understand patterns within the overall user base, and figure out the proportion of those using platform vs roaming authenticators, the transport mechanisms being used, as well as any other tendencies that may lend itself useful to running and maintaining a smooth authentication service.

Portable Root of Trust

Despite all of the obvious conveniences that come with a platform authenticator being integrated into a laptop or phone, it is important to also understand that roaming authenticators allow users a freedom of movement between different devices. Having a portable root of trust is essential in this regard, certainly for a percentage of the total users focused on security, and for enabling rapid bootstrapping on new devices, in addition to the ability to recover accounts quickly.

Tailored User Experience

Being able to include supporting text to guide users through a registration or authentication process is integral to a great UX. Armed with the data garnered from attestation for instance, it is possible to provide effective and targeted communications to each individual user based on their authenticator selection. For example, even if WebAuthn does not explicitly convey that biometric data is ever used to authenticate, it may be possible to extrapolate the fact from the attestation metadata regardless, and as a result, offer a way to address those specific users with pertinent information. This could lead to positive synergy where communication is enhanced and misconceptions are dismantled simultaneously, such as stating to users that fingerprint and face identification data is never transmitted across the network for their applicable devices.

Platform Authenticators as Trusted Devices

In the realm of traditional authentication the concept of Trusted Devices was introduced as a form of 2FA to make the login experience easier for a user who frequents a device. This often included the storage of a device identifier as a cookie, in cache, or in local storage. This presents an attack avenue, if an attacker gains access to a users computer, or finds a way to spoof the machine, then all they require is a compromised password to gain access to a users account. A Platform Authenticator can act as a Trusted Device by relying on the WebAuthn credential already built into the device. For an attacker it’s not just as easy as having access to the users device, they will also need knowledge of the users PIN, or access to the users biometrics (Fingerprint for Android Biometrics, Face for Face ID, etc.)